This is the 16th in a number of articles serializing The Sales Force — Working With Reps by Charles Cohon, MANA’s president and CEO. The entire book may be found in the member area of MANA’s website.

Harold complied, and said, “I’m going to add the words ‘commission system’ in parentheses underneath, because in every conversation we’ve had so far, commission has been the key element in getting the feedback you want.”

Jim agreed. “Harold, as long as we’re talking about things we want, you may as well write ‘more sales’ on the same page. And there’s something else on my wish list — surge capacity.” Harold added that note while Jim explained, “When we roll out a new item, we do it with the same-sized sales force we run with all year even though we really want to touch all of our customers with information about the new products in a hurry. Surge capacity would let us get more feet on the street talking about this new product while it was very new, but let our sales force revert to its normal size when the rollout is complete.”

This seemed like a tall order, and it stopped the conversation for a while. Finally Ruth spoke. “For you to get surge capacity, you’re probably talking about utilizing some outside company that would provide that service not just to Troothe, but to other manufacturers as well. Wait a minute, I think I can show you what I mean.” On her way to the conference room, Ruth had noticed an employee’s Yahtzee game sitting on one of the lunch tables. She retrieved it, and took the dice out of the box.

“Let’s say that in one month out of six we’re introducing a new product so we need extra feet on the street. To keep the math simple, let’s also say that the distribution of new product releases is random — in other words, every month we have a one in six chance of launching a new product regardless of whether or not we did a release the preceding month. In months when a new product isn’t released, a more modestly sized sales force is sufficient to support our efforts. A way to model this situation is to roll one die. If it comes up six, we have a new product to roll out and need extra sales help. Any other number is a normal month, without the need for extra headcount.”

Harold picked up on Ruth’s point almost immediately. “So, if two manufacturers were sharing this surge capacity system, then we’re rolling two dice, one for each manufacturer. If the first die comes up six, the first manufacturer needs surge capacity that month. If the second die comes up six, the second manufacturer needs surge capacity that month. And the chances of both coming up six the same roll, or the same month, are only one in 36. So, if two manufacturers shared their surge capacity, we would expect that on average only once in every 36 months would they both want to use that surge capacity during the same month.”

“That solves Troothe’s surge-capacity problem,” agreed Ruth, “but that business model isn’t going to be an attractive niche for some third-party company to fill. Let’s take a look at the math and see what would happen to a company that started up to provide surge capacity to companies like ours, but only had two clients. Statistically speaking, if you throw two dice there are 36 possible outcomes. In 25 of those outcomes there is no six, in 10 of those outcomes there is one six, and in one of those outcomes there are two sixes. So over time, we’d expect the surge capacity supplier to have no work to do 25 months out of 36, exactly the right amount of work to do 10 months out of 36 and too much work to do one month out of 36.” Harold and Jim both nodded, interested to see where Ruth’s argument was going.

“For this to make sense for the surge capacity supplier,” Ruth continued, “that supplier needs more clients. Just to illustrate, let’s take a look at the business model if we keep our other assumptions the same and increase the surge capacity company’s client roster to 12 manufacturers. Basic statistics tell us that the anticipated utilization of that outsourced surge capacity company’s services would be a binomial distribution.” Ruth picked up one of the markers and wrote:

Uncomfortable with math, Jim groaned theatrically when he saw the equation, but Ruth was intent on finishing her thought. “So, for example, the probability that the surge capacity supplier would have no products to introduce in any given month would be:

When Ruth paused, Jim spoke up. “Honey, you know me well enough to know that I am not going to follow the math, and I’m afraid if we get into this too deeply we’ll bog down this brainstorming session. Could we set this aside and come back to it?”

Ruth was steadfast. “Jim, there’s something valuable here that has a bearing on our discussion. Let’s take a 20 minute break and let me borrow the computer in your office to set up an Excel spreadsheet, and I promise I’ll come back with something right on point for this conversation.”

“I wouldn’t mind a break, myself,” Harold said. “Let’s get back together in 20 minutes or so.”

Jim was reluctant to lose the conversation’s momentum, but grudgingly agreed to the break. When they resumed, Ruth had written a table on one of the sheets of paper hung on the wall.

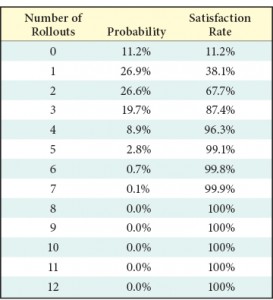

Once they’d settled back into their seats, Ruth picked up where she’d left off. “We spoke about how it would be valuable for a manufacturer to have an outside vendor to provide surge capacity when a new product is rolled out,” she said, “but we’d identified that providing this service would not be an attractive business model for a provider with only one or two clients. I’m suggesting we look at what it would take for that business model to work successfully so we can make the case to some outside company that it should start providing the service of which we’d like to take advantage. Based on what I found when I worked out this chart, I think the numbers look much better when that company’s client roster is larger — like the 12-client roster upon which I based this table.

“The most obvious benefit is that if a manufacturer like Troothe staffed adequately to handle a rollout but averaged only one rollout every six months, then the staff hired for rollouts would have no work to do five months out of six, or 83.3 percent of the time. Our outsourced rollout company with 12 clients will see months with no rollouts only 11.2 percent of the time, which is a real improvement in staff utilization.

“Now, let’s take a closer look at the chart. The first column is the number of clients that have scheduled a rollout in any given month. With 12 clients, it is possible that in January, for example, none of the clients would schedule a rollout, or one would, or two would or any number up to all 12 clients could schedule a rollout. The second column is the statistical likelihood that the number of rollouts in any given month would be the number in the first column. For example, the probability that exactly one company would have a rollout in any given month is 26.9 percent.

“The final column is a little trickier. It indicates the likelihood that all of the company’s clients’ requirements would be satisfied in any given month if the company staffed at that level. For example, if the company staffed adequately for one rollout, it would satisfy all of its clients’ needs in months where either zero or one rollout were needed, or 11.2%+26.9%=38.1% of the time. If they staffed for two simultaneous rollouts, they’d satisfy their customers any months where there were zero, one, or two rollouts, or 11.2%+26.9%+29.6%=67.7% of the time. A company staffed to handle three simultaneous rollouts would satisfy its 12 customers’ demands 11.2%+26.9%+29.6%+19.7%=87.4% of the time.

“Of course, we’re attributing accuracy of 0.1 percent to an example based on assumptions that easily could be 50 percent off, but it does illustrate the fundamentally sound economics of having one company provide the sales-surge capacity for a larger group of companies. As a matter of fact, one of the things that would make the economics even better than our example is that our assumptions describe a model in which all of the rollouts start on the first day of a month and end on the last day of the month. It is just as likely, though, that one manufacturer would roll out on the first of the month and another on the 15th of the month, so the overlap of those two rollouts would be only two weeks, which adds even more diversity to the system and would tend to smooth out the results even more.

“I realize I’ve taken us a little bit off the track as far as our brainstorming session goes, but I see a few other benefits in this model I’d like to mention before we go on. One is that as the number of rollouts for which you staff increases, you get added flexibility. For example, if you’re staffed for three rollouts and four hit at once, you could give each client ¾ of your staff and still maintain a pretty satisfactory service level.

“Another is that we’ve described surge capacity in terms of new product rollouts, but there are other ways this company could provide surge capacity to a manufacturer. Maybe Troothe had a new advertising campaign that created an unusually high number of inquiries from new customers, and we wanted to reply to each of them more quickly than our normal staffing could allow, or we’d just returned from a trade show and wanted to contact all of the visitors to our booth more quickly than our employees could manage. I’ll bet there are even more cases where having a versatile outsourced group that served the needs of 12 manufacturers like us easily could shift between serving our needs and the needs of its other clients.

“And finally,” said Ruth, “we also should consider the opposite of surge capacity. Let’s call it sag capacity. Say you’ve hit a dry spell, whether it’s a snag in production, a big order that overwhelmed plant capacity, a strike or a shortage of raw material, but regardless of the reason, you can’t take on other new orders for a while. Right now, you pay your sales force a fixed salary regardless of sales, and when the company’s income takes a dip you have to make a choice. Keep them on staff even though there’s very little for them to do or lay them off and face the expense of locating and training replacements when things pick up. And remember what happened the last time Bigglie had a layoff? You snapped up the salesperson they laid off and had the benefit of all the account knowledge he brought with him. Sag capacity would let you put your sales force in ‘suspended animation’ when they weren’t needed, and yet they’d be ready to pick up right back where they left off when you were ready to start booking new orders again. If our outsourced surge capacity supplier had 12 clients and one went off line for a while, it could avoid layoffs by diverting its attention to the other 11 and then resuming service to client 12 with little loss of momentum when that client went back on line.”

Harold wrote “Sag Capacity” under “Surge Capacity” on the sheet, and had a new point. “Whatever this system is, it should be scalable.” Jim looked puzzled. “By that I mean, if you come up with an arrangement that works for one person or a handful but falls apart when you try to use it over a larger system, then it isn’t scalable. I can see two issues of scalability, financial and geographic. On the financial side, if we create a system that works while we have sales of $10,000,000 but will fall apart when our sales hit $100,000,000, then it isn’t scalable financially. And we need to be geographically scalable too, so it will work all across the country.” Harold wrote the word “scalable” on the sheet, with arrows leading to “financially” and “geographically.”

To be continued next month.

MANA welcomes your comments on this article. Write to us at [email protected].