This is the third in a number of articles serializing The Sales Force — Working With Reps by Charles Cohon, MANA’s president and CEO. The entire book may be found in the member area of MANA’s website.

Interrupted only by the arrival of box lunches at noon, the council worked straight through until 4 p.m., when Jim arrived to receive the group’s recommendations. Maria had been chosen to present the group’s findings and was standing next to the overhead projector when he walked into the conference room. Jim sat down in the front row, but Maria made no move to turn on the projector.

“Jim, first let me say on behalf of the group that we appreciate Bigglie’s bringing us here. I realize that you were called in at the last minute because you lost your sales manager, but we are concerned that no one from the management team could break away to meet with us. We have two issues that bubbled to the top, and we are relying on you to get management’s ear with these.”

“Well, Maria,” Jim said, letting a little irritation creep into his voice, “I am sure the management team would have been here if it had been possible. All I can do is my best, and we’ll just have to hope that it is enough.” He thought to himself, “It’s bad enough that my career has stalled on the low end of the organization chart without also having my nose rubbed in it in front of our 10 largest distributors. What a charming way to cap off another fun day at the office.”

“Jim, we have two issues: minimum billing and salespeople’s compensation. Minimum billing is a no-brainer, so let’s start there. Bigglie implemented $100 minimum billing last year.” Jim knew the company line on this, so he was ready to reply.

“Maria, it costs us $25 to issue an invoice. So right away a $100 order turns into $75. Throw in our cost for product and packaging, and we are losing money even on a $100 order. Management has done the calculations — if we could throw every $100 order out the window instead of filling it, we’d make a lot more money. So taking orders under $100 is out of the question.”

Maria smiled. “So, now that you stopped filling orders under $100, who were you able to fire to save money because you no longer accept all of those unprofitable orders?”1

“We didn’t fire anyone, Maria,” Jim replied. “That wasn’t the idea.”

“I’m just trying to figure out how you saved money,” Maria explained. “If you didn’t fire anyone, apparently you were able to take some computer hardware off line and sell it off, then? Is that how you saved money?”

Jim stopped to think. He wasn’t wired tightly into the goings-on in the computer department, but he didn’t think any equipment had been unplugged. Plus, how much does used computer equipment sell for? She could see that her points were sinking in, so Maria paused before continuing. “I know that this is going to be hard to swallow, but if you take a close look you will find that minimum billing actually is costing Bigglie money.”

“Costing us money?” Jim unconsciously rolled his eyes before he could catch himself and regain his professional poker face. “Maria, even though I can’t point to where minimum billing shows up as savings on the bottom line, I don’t see how minimum billing can cost us money.”

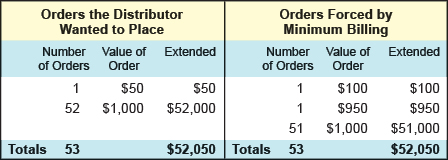

“The key is to remember that you are dealing with distributors who purchase your product every week, or perhaps every couple of days,” Maria said. “If you were making a one-time transaction with a customer you would never deal with again, you absolutely would have to cover all your costs and make a profit on every invoice. But let’s take a look at the two possible scenarios that can occur when one of your distributors goes ‘stock out’ on an item and wants to place a $50 order. To make the example simple, let’s say that this distributor normally gives you a $1,000 order once a week and that there is only one ‘stock out’ this year.

“The first possibility is that the distributor goes ahead and buys another $50 worth of product that he would have bought later in the month anyway. So for one week this year, your customer buys that special $50 item plus another $50 item that he would have bought next week anyway. The order next week is $950 instead of $1,000.” She turned on the projector, and a neat though hand-drawn chart filled the screen. “Let’s look at this on a chart and see what the difference is to Bigglie.”

“With or without minimum billing, you process 53 invoices totaling $52,050,” Maria continued. “What is the point of inconveniencing your distributors just so you can process exactly the same number of invoices with the same total dollar value you would have handled anyway? And this is the best-case scenario. Let’s stop and take a look at what happens if the distributor makes a bad guess on which part to buy to gross the order up to $100.

“Normally our orders are based on some fairly sophisticated replenishment software, but when we are rushing to add $50 worth of material, it is more likely somebody will choose incorrectly and buy something that ends up as $50 worth of dead stock. Every year your distributors have stock rotation privileges equal to five percent of total sales. You forced us to buy $50 outside our normal purchasing routine, creating a mistake we otherwise wouldn’t have made. When we return this $50 in dead stock forced on us by minimum billing, Bigglie has to do incoming receiving and inspection on this part, and return it to stock. All the costs Bigglie has to eat to take this part back are the result of your minimum billing policy, and you also are putting a part with a six- to 12-month-old date code back on your shelf.”

Maria paused again to give Jim a chance to absorb her argument. As the silence continued, Maria forced herself to stay quiet, remembering that allowing an extended silence often will work to a negotiator’s advantage.

“Maria, this really flies in the face of normal practice, but I can’t see any flaws in your argument. I am going to have to give this a little more thought to be sure I haven’t missed anything, but it sounds pretty convincing to me.”

Maria stood and handed Jim two sheets of paper. “Here is a copy of the chart and the bullet points. If you think of anything that would prevent you from making this case to management, I really would appreciate the opportunity to discuss any concerns that come up.”

“Fair enough, Maria. Now you said you had an issue with salespeople’s compensation….” Jim’s voice trailed off as he sat down.

“This one is a little trickier. We have a problem but not a solution. We’re hoping that, if we can explain what’s been going on, Bigglie can figure out how to deal with it. Bigglie has compensated salespeople several different ways in the last few years. In each case, your people have done what the system has told them to do, and it hasn’t been good for your distributors or for Bigglie.

“Bigglie’s first compensation system paid each Bigglie salesperson based on what each one sold directly to large customers. Almost as an afterthought, each of your distributors was assigned to a particular Bigglie salesperson, and that salesperson received commission based on whatever his or her assigned distributors purchased. When my distributorship sold a flange to customer A, I replenished my stock and my Bigglie salesman Sam got paid based on what I bought from Bigglie. If customer A bought from a distributor assigned to Bigglie salesperson Lois instead, that distributor replenished its stock and Lois got credit for a sale to that distributor. So, Sam tried to steer customers to me, and Lois tried to steer customers to her assigned distributors. Even worse, Lois got her distributor special discounts so they could steal my customers, and Sam reciprocated with even deeper discounts. So a $4 flange became a $3.50 flange, and then a $3.10 flange, and then a $2.90 flange. Pretty soon Sam started pressuring me to slash my profit margin to take customers away from Lois’ distributor, and Lois undoubtedly was doing the same to her distributors. This puts both prices and profit margins on Bigglie products into a death spiral, so we didn’t have much incentive to promote Bigglie flanges any more.

“Your next sales manager put all distributor sales into a pool,” Maria continued, “so each of your salespeople shared the credit when any of your distributors sold a Bigglie product. It sounded good at first, but it didn’t take long for your salespeople to figure out that when an order was referred to a distributor, the commission was shared with nine other salespeople. When an order bypassed the distributor and went right to Bigglie, they received all of the commission. Bigglie salespeople started stealing your distributors’ customers, because a $1,000 sale to a distributor meant sales commission on what amounts to a $100 sale, but a $1,000 direct sale meant commission on $1,000. With your salespeople stealing our customers, we couldn’t rely on them to help us anymore, and Bigglie ended up filling directly many small orders that a distributor should have been servicing, because that was the way your people could maximize commissions.”

Maria paused for a sip of water before continuing. “I have talked to friends who live more in the electronics world than the flange world, and they have a different way to deal with these problems, but I don’t care for it much. They call Bigglie’s current system a Point of Purchase commission system, or P.O.P.2 because it is based on a distributor’s purchases.

“Their system is called Point of Sale or P.O.S. because it is based on what the distributors sell. The electronic distributors supply the manufacturers with a monthly report of everything they sold and to whom it was sold. The manufacturer pays its salespeople based on the distributor’s report of where the distributor sold product instead of what the distributor buys. If Bigglie used this system and Sam has worked on a medium-sized OEM customer that ultimately ends up buying from me, Sam gets paid. If that customer buys from a different distributor, Sam still gets paid, because that distributor reports the sale that was made to Sam’s customer. This breaks the linkage between Sam and any one distributor. Any distributor selling to Sam’s customer can get Sam’s support because Sam gets paid no matter which distributor services the account. And Lois can’t steal Sam’s customers by offering a lower price, because all of Sam’s customers are tied to Sam by the distributor’s P.O.S. report.

“This solves some of the problems, but there are some aspects of this kind of reporting that make the hair on the back of my neck stand up. And I will apologize up front for what I’m about to say, but the distributor council doesn’t help you if it isn’t candid. With your revolving door for salespeople and sales managers, we would be very reluctant to give you a report of everything we sell and to whom we sell it. I mean, let’s face it, some of your salespeople and at least one of your sales managers have ended up with flange companies or distributors I have to compete with every day. I can’t risk giving you detailed information about my customers if salespeople and sales managers can walk out your door with that kind of information about my business. So, what I am telling you is: We have identified the problem and three solutions that don’t work. The ball is in your court, Jim.”

Jim was uneasy. He felt that he could make a pretty good presentation to David Buchanan on minimum billing, but going to Buchanan with a problem that didn’t include a solution worried him. “Duly noted, Maria,” he replied. “I will see what I can do.”

To be continued next month.

1 A tip of the hat to Eliyahu M. Goldratt’s The Goal: A Process of Continuing Improvement (Great Barrington, MA: The North River Press) p. 28 where a similar point was made regarding the “savings” achieved by factory automation that did not replace any employees or any other equipment.

2 Charles M. Cohon, “The Positives of POS Data,” Electrical Wholesaling, January 2000, p. 23-24.

MANA welcomes your comments on this article. Write to us at [email protected].