This is the seventh in a number of articles serializing The Sales Force — Working With Reps by Charles Cohon, MANA’s president and CEO. The entire book may be found in the member area of MANA’s website.

Jim had welcomed the opportunity to adjourn their meeting for lunch. Harold’s arguments all had been logical and Jim could find no flaws in Harold’s reasoning, but Jim could not bring himself to abandon the natural intuition that a commission system was necessary to drive a sales force. By the time the two men returned to Harold’s office, the break had given Jim enough time to put his finger on what was bothering him.

“We’ve always managed our sales forces with rewards and fear, Harold. Carrots and sticks. You proved that for all salespeople whose results are within the system, the relative differences in their results do not give us any evidence of a difference in their contribution. From the standpoint of fairness, it may bother us that salespeople who make the same contribution can end up with very different sales commissions, but life isn’t always fair. You are missing the significance of a point you made yourself — salespeople don’t understand statistics. It may sound manipulative, but as long as the salespeople think that their commissions are a result of their efforts, they will keep trying. Salespeople chase commissions like greyhounds chase a mechanical rabbit. Without the prospect of a reward, why would the salesperson chase orders?”

“Jim, I see your point, but let’s take a closer look. What you’re really saying is we want the salespeople to give the company the greatest effort possible. We want them to try really hard. After we award one of our random rewards, the person who received it works really hard to do the same thing again, and the people who see the award being assigned work really hard to emulate that person’s activities. But remember, the award was assigned based on a random event. A salesperson who tries to earn a repeat award by doing the things that seemed to trigger the winning results isn’t likely to get the same outcome a second time. Other salespeople who try to copy the winner can’t find the winning formula either, because there isn’t one.

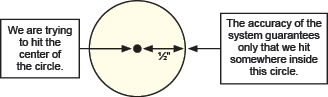

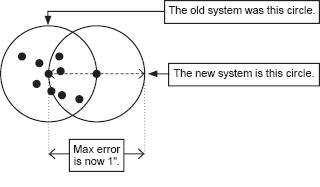

“I think I can illustrate what is happening here by taking another example from the plant,” said Harold. “We’re drilling holes again. The goal is to drill the hole in a particular spot. Variables in the material, machinery and operators form a system in which any result where the hole is within one half-inch of the target is within the system. To illustrate this system, I can draw a circle with the target at its center and a radius of one half-inch. Of course, the diameter of the circle is twice the radius, or one inch. Let’s take a look at the system:

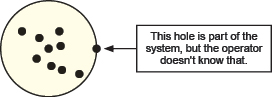

“We’re chugging along with a reasonable distribution of holes, and then the operator sees that we have drilled a hole a half inch to the right of the center:

“The operator doesn’t know about variances or distributions, all he knows is that the hole he just drilled is one-half inch to the right of the spot he was trying to hit. If the machine drilled a hole one-half inch to the right of the desired spot, intuition tells him to move the drill head one-half inch to the left.1 After all, if the drill head had been one-half inch to the left when the last hole was drilled, that hole would have been right on target. When the operator moves the drill head, he moves the whole system a half-inch to the left:

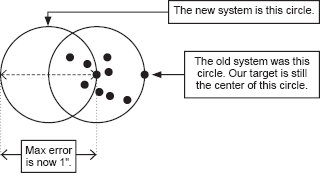

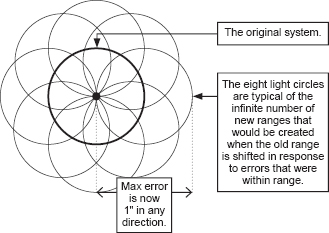

“After that change, the only time we hit the original target exactly is when we are at the point of the new system farthest to the right. If we hit the point farthest to the left in the new system, we are one inch to the left of the target, a much greater error than we could have made if we had left the system alone. Eventually, we will hit that point one inch to the left of the target, and the operator will curse the inaccurate machinery with which management forces him to work. They are lucky to have such a clever machinist operating the machine, he decides, so he moves the drill head one inch to the right:

“Of course, the errors don’t occur just to the left and right. Each time a hole is created at the outer edge of the system, the operator compensates by moving the system a half inch in the opposite direction. Over time, a hole is drilled at every possible point at the perimeter of the original system, so the operator’s range of corrections looks like this:

“The areas of the circles describing the old and new ranges are worth noting. In the old system, the range was a circle with a radius of one-half inch, so the area of the circle is πR2, roughly 0.79 square inches. The new circle with a one-inch radius encloses an area of 3.1 inches; so doubling the radius means the area that describes all of the potential outcomes is four times larger.

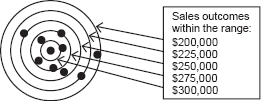

“How does this apply to a salesperson? Let’s look at a group of salespeople’s outcomes and find out:

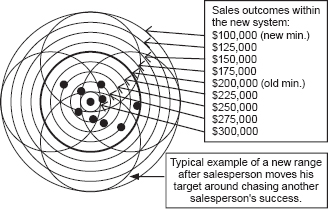

“In this example, any outcome from $200,000 to $300,000 in annual sales is within the system. As we already discussed, differences in results within the system do not give us any evidence of differences in the efforts or skills of the employee. Fairness would dictate that employees who contribute the same level of effort and skill receive the same compensation, and statistics tell us that nothing in these sales figures identifies a difference in the salespeople’s contributions. But you said it earlier — life is not fair. It’s inevitable that the $200,000 commissioned salesperson will try to emulate the $300,000 salesperson’s success because the $300,000 salesperson received 50 percent more income. We just need to know if it hurts the company when a commissioned salesperson compensates in the same intuitive fashion as our drill operator,” Harold said.

“To get the answer we have to remember that there is no statistical evidence that the $300,000 salesperson’s skills or efforts did anything to contribute to the difference between his results and the $200,000 salesperson’s results. So there is no reason to think that whatever characteristics the $200,000 salesperson chooses to copy from the $300,000 salesperson were in any way responsible for the differences in their outcomes. When the $200,000 salesperson decides to concentrate on the food service industry because the $300,000 salesperson concentrates there, he may be ignoring the fact that the $300,000 salesperson’s territory includes more food service companies than his territory. Perhaps the $300,000 salesperson spends more time taking customers golfing. The $200,000 salesperson might do the same, but he will be chasing one random attribute from a salesperson whose apparent advantage actually falls within the same system as his own. This is no different from the drill operator who adjusted his machinery when a hole fell one-half inch from the target. When a salesperson makes random alterations to his system, he will experience the same effect as the drill operator did — outcomes that range farther from the target than they did before the adjustment.

“The area of our new circle is four times the area of the old circle. If we were shooting arrows at this target, three out of four spots where our arrow can land are worse than our situation before we started moving the center of our system,” Harold finished.

“Harold, I have a big problem,” Jim said. “Frankly it’s not with your logic, it’s with how this would impact me. I want to be the new sales manager, but from what you’re telling me, it sounds like there really isn’t a sales manager job left. A major part of most sales managers’ jobs is riding the salespeople who have lower sales, but if they are within the system then it isn’t their fault and there is nothing for me to fix. The sales manager is supposed to reward top performers, but if the top performers are within the system, they haven’t done anything to justify a reward. Sales managers are responsible for tweaking the compensation system, but you’re telling me that moving the targets around increases the size of the system and means we’ll end up farther from the targets than we would have otherwise. And, normally, the sales manager takes responsibility to direct salespeople to change the mix of accounts on which they call, but you’re saying that increases the size of the system too. So if there is a job for a sales manager, what is it exactly?”

Harold smiled. Jim seemed to really understand and embrace the concepts Harold had been explaining. “Jim, let’s look at this in terms of the marbles and paddles. We want to pull out more white marbles. How can the sales manager make that happen when the paddles are all within the system? The traditional answer is to push the salespeople to make more calls; in other words, to make the paddles bigger so there can be more dimples to hold marbles. More dimples mean more white marbles — but of course also more red marbles. This is a productive use of the sales manager’s time only if the salespeople are not already working as hard as they could be — in other words, if you hired lazy salespeople, you will need to spend your time trying to force them to put in a full day’s work.

“Let’s rephrase this — you did such a bad job of hiring these salespeople that now it is a daily struggle to get them to do their jobs. If you had hired salespeople with a good work ethic, they already would be putting in a full day. Any possible incremental gain you could get from whipping them is overwhelmed by the reduced effort you probably will get when they will come to resent your badgering. A sales manager who can’t identify candidates with a good work ethic ought to be fired and replaced with someone who can,” Harold said.

“This doesn’t sound like very good job security for the sales manager,” Jim said. “It sounds like once the sales manager has hired bright, hard-working salespeople, his job is done.”

“Not at all,” Harold replied. “What the sales manager needs to work on is the system. In our paddle example, if we already are drawing the maximum number of marbles, and we want more of the white marbles, how does the sales manager accomplish this? By eliminating red marbles! Red marbles are things that kill a sale, or prevent repeat orders or create returns. For example, a sales manager needs to monitor the customer service department’s responsiveness in providing answers to customers’ inquiries. Are there problem areas — red marbles — to be addressed? For example, has customer service been supplied with tools like cross-references that enable them to supply our equivalents to another manufacturer’s part while the customer still is on the line? Are price and availability information easily accessible? Do we promptly acknowledge orders and provide our customers with tracking numbers? Are we open during the normal business hours of all of our customers, regardless of their time zone? Do our customer service reps remember to thank customers for their orders, and maintain a friendly and helpful demeanor? Are we packaging our products so they aren’t damaged in transit? If we don’t at least match our competitors in all of these areas, we have an avoidably large number of red marbles, and the salespeople will draw fewer white marbles as a result.

“In the example of shooting arrows at a target, we see another illustration of the sales manager’s job,” said Harold. “Any time we fire an arrow at a target that represents a system, the arrow lands somewhere on that target. Exactly where it hits the target will vary based on the characteristics of the system, but we want to shoot as many arrows as possible. We don’t accomplish this by dumping a pile of straight and crooked arrows next to the salesperson and forcing him to search for a straight arrow before every shot. This is what we do when we dump a stack of unqualified sales leads on an outside salesperson. The sales manager can establish a system where staff people qualify leads before the salesperson ever sees them. If you hand the salesperson a quiver of straight arrows before he steps up to shoot, he will get off more shots and naturally will succeed more frequently.

“Another way the sales manager can help is to be sure that outside salespeople are outside selling while clerical tasks are given to clerks. If salespeople can’t rely on the clerical staff to get quotes completed in a timely and accurate fashion, the sales manager needs to intervene. The sales manager naturally takes the point position on implementing sales force automation and sales force training. And, of course, by making joint calls on key accounts with the salespeople, the sales manager learns about common customer needs that cross salespeople’s territorial borders, the kind of marketing information that is critical to planning new Bigglie product offerings. There is plenty for a sales manager to do,” Harold concluded.

“I’m getting it now,” said Jim. “I’ll add to that marble analogy. The sales manager’s job of removing red marbles from the bin is very different from one way sales managers often spend their time: bouncing salespeople from objective to objective. Something like, ‘let’s concentrate on machine tools this week,’ then ‘let’s concentrate on conveyors next week.’ Or maybe, ‘let’s focus on new accounts this month’ and then ‘let’s focus on current accounts,’ followed by ‘let’s focus on big accounts’ and then ‘let’s focus on small accounts.’

“Re-tasking the sales force looks good on the sales manager’s reports to upper management,” Jim continued, “but it isn’t adding productivity — it’s just moving salespeople around from one marble bin to the next. And we’ve seen what happens when variability is added to the dynamics of a sales force — sales results go down. Maybe upper management brings this on itself. If they want to see something new and dramatic in the sales manager’s strategy report every month, the sales manager will learn to accommodate them, so nobody concentrates on pulling out the red marbles,” Jim said.

“And that reminds me,” Jim added, “there is one special red marble that drives me nuts: running out of sales literature. The sales manager should remind management of the waste created when a sales call that consumes $500 worth of a salesperson’s time is undermined by the lack of $20 worth of support material.

“But it’s even worse than that. Once the salesperson survives one literature drought, he becomes a literature hoarder. When materials become available again, he’ll take three or four boxes to stash in his garage as back up for next time we run out of literature. If we come out with updated literature before the supply in his garage is used, his stash gets heaved into a dumpster. With each salesperson hoarding three or four cases of literature, a big piece of our printing budget may end up in a landfill — all because the salespeople don’t trust their company to keep literature in stock. Fixing that problem won’t make a very exciting bullet point for the sales manager to kick upstairs to top management, but all the money that was saved by keeping literature readily available will go right to the bottom line,” Jim concluded.

Harold nodded. “The biggest challenge for a sales manager is that careful hiring, removing obstacles, and listening for new opportunities is not sexy or dramatic. It’s hard for a sales manager to look the CEO in the eye and say, ‘This month I carefully avoided hastily hiring the wrong guy, worked to eliminate a bottleneck in customer service and went on sales calls with 10 of our salespeople.’ ‘Yes,’ says the unenlightened CEO, ‘but what did you accomplish?’

“Compare that with telling the CEO, ‘I fired two salespeople because their numbers were down, created a new compensation plan that will really fire up the sales force, and gave American Express gift checks to our top-performing salespeople.’ ‘Way to go, Bob,’ says the CEO, ‘Good job of managing!’ It’s going to take some work to convince upper management that doing the things that are in the company’s best interest won’t make for a dynamic report, but if we want white marbles to replace the red ones, then in the long run somebody has to do the unglamorous heavy lifting.”

Harold paused. “We’ve gotten a little bit off target talking about the sales manager’s responsibilities. What we are supposed to be doing is coming up with a solution to the compensation problems that came from the distributor council. I think we’ve pretty well established that a salaried sales force would answer those concerns, but Buchanan told us not to bring him a solution unless we get buy-in from the distributor council. You know the Gonzales’ pretty well and I don’t know them at all. I’m going to leave that step to you. If they think this is the solution, then we can present it to Buchanan.”

“OK, Harold, but I don’t feel like I could make as statistically compelling an argument as you did. If you’ll get the PowerPoint presentation ready, I’ll go and present it to Enrique and Maria,” Jim said.

“Done,” replied Harold.

To be continued next month.

1Harold knows that the fixtures securing the workpiece rather than the drill head are what would be adjusted, but ignores that fact to avoid bogging down his explanation.

MANA welcomes your comments on this article. Write to us at [email protected].