This is the 19th in a number of articles serializing The Sales Force — Working With Reps by Charles Cohon, MANA’s president and CEO. The entire book may be found in the member area of MANA’s website.

“Fred, I have to admit there are some attractive features you may be able to offer your employees that we can’t at the factory. Anything else before you let me buy you some lunch?”

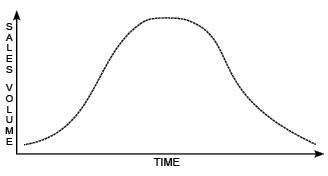

“Just one thing,” said Fred, who had warmed to the topic of promoting the rep system. He pulled out a legal pad and made a quick sketch.

“I think you’ve probably had the same experience as the rest of us,” Fred continued. “In your relationship with a customer, you usually start off with very low sales, work hard to build that business to a good level, hold it at that level as long as you can, and eventually it tapers off. Even to a customer your company has served for years, sales will taper off eventually, if for no other reason than perhaps you discontinue one model and convince them to accept the new one. When you do, the old model follows this curve and the new one picks up where the old one left off.”

Jim nodded, but was puzzled, not seeing where Fred was going. Fred grabbed a thick marker off his desk and drew another curve on the graph.

With great enthusiasm, Fred explained the second curve. “Some of the ways the rep can increase his income are to make the early part of the curve ramp up more quickly, or hold the curve at its highest point for a longer period of time, or make the end of the curve slope down more gradually. After all, a rep’s income is directly proportional to sales, and in this graph the total sales are equal to the area under the curve, so the rep’s total income as a percentage of those sales is proportional to the area under that curve.

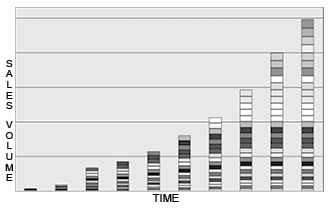

“The neat thing about the rep system,” Fred continued, “is that we have many customers, so we have many curves. We spend a lot of time developing new customers, investing time and money at the low end of the curve, because we know we’ll reap the benefits later on. In a lot of ways, it’s the inverse of standard practice in corporate America, where they live and die by quarterly results. That’s one element of what makes the rep business attractive — the opportunity to enjoy a long-term payoff. So let’s look at this same graph with lots of customers plotted on it.

“Here, the curves all have different peaks, stay at their peaks for different lengths of time and have different slopes going up and down. It’s the very fact that these slopes are randomly distributed that helps make the rep business model attractive. It’s the sort of distribution stock analysts refer to as uncorrelated — while some go up, others go down, and others remain flat. Many fund managers try to choose a portfolio of stocks with uncorrelated results in order to achieve a more stable rate of return. For the same reason, a portfolio of customers whose purchases all are at different stages of their life cycle (starting, going up, holding at the top, going down) will allow a rep’s income to be more stable. And the beauty of this system is that in any given month, the sum of the distances between each curve and the X axis represents the total sales achieved by the rep company. Again, with commission a direct percentage of sales, multiplying each of those distances times the commission rate calculates total commission revenue for that period. Especially appealing to the rep is the fact that income can be increased by:

- Adding a curve to the graph.

- Making a curve slope up more quickly.

- Holding a curve at the top longer.

- Making a curve’s eventual fall a more gradual slope.

“It’s the opposite of what you see at public companies, where it is almost standard practice to steal from next quarter’s sales to make this quarter’s forecast. The rep makes an up-front effort with the expectation that future rewards will follow. The effect of a rep’s continuing effort in his or her territory is best illustrated by a histogram. First, let’s go back to the curves I drew a few minutes ago. The rep’s income at any point in time is just the sum of all the distances from every curve to the X axis. Translating that information into a histogram, you can see that the rep’s income tends to grow over time, and the business he or she achieves has enough diversity that no one customer or principal can put the rep company’s survival at risk.

“I realize that I had a lot to say,” Fred apologized, “but before we go down to lunch, I’d like to share a great quote I found that has a bearing on this. Some of the folks who work in manufacturing feel that their companies are so big and reps are so small that the reps have nothing to offer. To such a person I’d quote Sun Tzu: ‘He who understands how to use both large and small forces will be victorious.’”1

After meeting with Fred Richardson, Jim was eager to take the next step toward working with manufacturers’ representatives, so he looked in on Harold to bring him up to date and discuss how he should proceed. After Jim reported his findings, he said, “I think the next step is to talk to some reps so I can gather the information I’ll need to build a case for Joe Troothe that the rep system would pay for itself in increased sales while getting us the feedback we need.”

Harold agreed, commenting, “No harm in talking to some of them. By the way, how exactly do you go about finding suitable rep companies?”

Jim shifted uncomfortably in his chair. “Good question. Wait, I’ve got it. Our competitors have websites. If I go to their websites, maybe I can find a listing of their reps, perhaps even including their email addresses. Then I can send out an email to the whole group inviting them to apply to represent us. This is going to be great.”

Jim was successful in locating the names of 32 companies representing various competitors, but that was where his success ended. His broadcast email netted only three responses, and all were polite but firm in their reply — “We appreciate your interest, but we already represent a competing line so we could not be candidates to represent your products.”

Later, Harold and Jim puzzled over Jim’s unsuccessful email campaign. “I don’t get it, Jim,” Harold said. “We’re a good company — why wouldn’t these reps jump at the chance to talk to us?”

Jim nodded. “I’m stuck, too. If you and I can’t figure this out, where do we go for help?”

Neither man spoke for about a minute. Harold tented his fingers, and then offered an idea. “You never had a conversation with any of the companies you tried to recruit, did you, Jim?”

“No. I was waiting for them to call me in reply to my email, and no one ever did.”

“Why not a pick one of the companies that declined politely and give them a call to find out why they declined?” Harold asked.

Jim smacked himself in the forehead with the palm of his right hand. “Of course. I was so sure there would be a stampede to represent a great company like ours that I thought I’d wait for the reps to contact us. Looks like I need to be a little more proactive.”

Jim’s first call the next morning caught rep company owner Sue Elliot in her office at 7:45 a.m. “Hi, Sue, this is Jim Anderson from Troothe Products. You were kind enough to give me a very polite reply to my recent email. I was hoping to speak to you about that briefly.”

“Hi, Jim. As I said, I appreciate your interest in our company, but we have a long-standing relationship with one of your competitors, so we really couldn’t talk to you about making a change at this time.”

“I understand, Sue, and I appreciate your candor. I was just hoping to speak with you for a few minutes anyway.”

“Well, Jim, if I can’t offer my company’s services to you as a representative, what exactly can I do for you today?”

“I’m new to the whole concept of manufacturers’ reps, Sue, and I’m not having any luck finding reps willing to speak with me. You saw the email I sent. I was hoping you could tell me why I got only three replies from 32 emails, and all three of those were a polite ‘no thanks.’”

“Jim, I don’t know where to start. How thick-skinned are you? If you don’t mind a really blunt critique, I can give you a few minutes, but I’m not sure you would like what I have to say.”

“Please, if you would be brutal I would really appreciate it.”

“OK. First, the bulk email you sent was addressed to 32 rep companies, including my own. It was pretty obvious you were just throwing the email up against the wall to see if anything would stick. My company is well established and has a great reputation, so we get 20 to 30 emails from companies looking for reps every month. One of the first screening processes we apply to determine which companies we consider as potential principals is whether the company sending the email appears to have done enough research to identify that my company would be a good choice for their short list of potential reps. The bulk email you sent to us made it pretty obvious you had not done any research before the email went out.

“I don’t think we’ve ever received a viable inquiry from a prospective principal that started as an email,” she continued. “Manufacturers that have done the research to find us and identify that we are one of the premier reps in this territory generally pick up the phone and call us. The other problem with your email is that it was pretty clear you were attempting to recruit from a competing manufacturer’s rep list, which is one of the worst lists from which you could have started. We and most other manufacturers’ reps usually have long-standing relationships with our principals — and a lot of times we’re personal friends with key executives of the companies we represent. To convince a rep to switch from an existing principal to your company, you’re going to need an extremely compelling argument. And there’s also a question of professionalism involved. Grabbing a list of other manufacturers’ reps off their websites is not all that different from taking a company directory from one of your competitors and making a blanket solicitation of all its employees. How would you react if one of your competitors sent individual invitations to everyone who works at Troothe to come to work for them? It’s more than bad manners, it also shows you’re not very discriminating about who you solicit — if you work for a competitor, you’re automatically in contention. And what does it tell you about the character of the respondent if they’re ready to jump ship on the strength of an email and a follow-up phone call?”

Jim was taken aback by the directness of Sue’s comments, but it was information he felt he needed, so when she asked if she should continue, Jim said, “If there’s anything more I should hear, please go right ahead.”

“I’ve sold flanges for a while, so I’ve got friends in this industry. Before I replied to your email, I had a friendly chat with a distributor we have in common. I was told that you have a good company, but your catalog is out of print. If you did hire me as a rep, would you expect me to go out on sales calls and paint a word picture of your product?”

Discovering his catalog woes were common knowledge with his competitors made Jim wince. “Sue, you sure kept your promise to be direct. If we speak again I may ask you to sugar-coat things for me a bit,” Jim joked.

“I’m a little surprised at how well you take criticism,” Sue replied. “It sounds like you are sincerely interested in learning about the rep system, but that your lack of experience is tripping you up. Frankly, I don’t want to help you compete with me, but our rep associations make the point that when a manufacturer moves from a direct sales force to reps it increases the pool of principals available to all of us, so I’ll give you a couple of pointers before I get back to work.”

“First, you need to learn more about the rep system before you contact any more reps. For general information your best resource would be www.MANAonline.org. You need to be able speak intelligently to potential reps on topics like the terms of your rep agreement, and how you handle commission splits and point of sale. And get your catalog printed. The first thing any rep will want to see is the collateral material and sales tools you have available, and at this point your cupboard is bare.”

“I promise to do my homework before I contact any more reps,” Jim said. “But how do I find the right reps?”

“The best resource you have to find appropriate reps is asking your existing customers. Of course, you’ll want to ask the distributors, but the OEMs (Original Equipment Manufacturers) should be consulted as well. Not just the purchasing agents — in a lot of cases they are buying the brand that’s specified by engineering, so you want to ask the engineers what reps are influential with them. Remember, when you try to get reps to switch principals, you start with two strikes against you, so your best bet is to look for reps who sell products that are complementary to flanges, but don’t already represent a flange manufacturer. I’ll even tell you how to find that kind of rep. There is a list of my lines on my website. Go to the websites of other manufacturers on my line card and look at their rep list. Then visit their reps’ websites, look for the ones that don’t have a line of flanges, and pick up the phone and call them. No more emails.

“Now, before I get back to work I’ll give you one last bit of advice. Start slowly. No matter how much you think you can learn about the rep system from the outside looking in, there are nuances you only can learn by working with reps. If you start with one or two reps you’ll only make those mistakes with one or two reps. Start with 20 reps, and you’ll make those mistakes with all 20. And, you’ll have to get buy-in from Troothe’s existing employees — it’d be easy for a few committed foot-draggers to sabotage the whole process. Don’t forget what Machiavelli said about change: ‘…he who introduces it makes enemies of those who derived advantage from the old order and finds but lukewarm defenders among those who stand to gain from the new one.’” 2

“Wow,” said Jim. “That’s a lot to absorb, but it makes sense. I really do appreciate your help, Sue.”

To be continued next month.

MANA welcomes your comments on this article. Write to us at [email protected].

1 SunTzu, The Art of War, Samuel B. Griffith translation (London: Oxford University Press) p. 82.

2 Nicollo Machiavelli, The Prince, Daniel Donno translation (New York: Bantam Dell, 2003) p. 31.