This is the 24th in a number of articles serializing The Sales Force — Working With Reps by Charles Cohon, MANA’s president and CEO. The entire book may be found in the member area of MANA’s website.

“I didn’t see a ‘Life of Part/Life of Program’ clause in the agreement, and I’d like to see it added,” William replied.

“What is that?” Jim asked. He felt the discussion between William and Joe was not going well, and he was hoping to interject himself as a mediator.

“Most reps and manufacturers refer to it as a LOP/LOP clause,” said William, “and it’s pretty standard in industries with long design cycles. It’s designed to give reps who spend a long period of time working on a sale reassurance that an unforeseen termination of the rep agreement won’t prevent the rep from receiving compensation for that long effort. Let’s take as an example a new opportunity to sell Troothe products that my company identifies, and for the sake of this discussion let’s say we identified it on January 1st. We invest a tremendous amount of time and energy working with this prospective customer, and by November the customer completes the design with a Troothe flange as a component in his product, so the sale is a foregone conclusion. In December we get a prototype order, which ships a month later in January. The prototypes work well, and we get a production order two months later, in March. Production quantities ship in May, which is 17 months after we started the process.

The next month something happens, and our contract is terminated. It wouldn’t have to be our fault — maybe your company is so successful that you get a cash offer you can’t refuse from a Fortune 500 company. After 17 months of work we get commission on 30 days of production. This wouldn’t be fair to my company or my employees, so we always include a LOP/LOP clause in every new contract we sign.”

“Isn’t that the risk you take when you become a rep — a 30-day cancellation term is what’s supposed to keep you sharp, isn’t it?” said Joe. William started to reply, but Joe interrupted his response. “And besides that, if you were terminated and we hired a new rep, that new rep would expect to enjoy the commission on our existing business just like you’re asking to enjoy our existing business, so that would mean we couldn’t pay our new rep for the account if we were paying you.”

“Actually, paying us would help you when it comes time to hire your next rep,” William said. “One of the things a potential rep is going to look at as he or she considers your line is how you treated the rep that was terminated. They assume that if and when the time comes to terminate them, they’ll be treated the same way you treated the last rep you terminated. Of course, they’ll want a Life of Part/ Life of Product clause, too, and they’ll consider your performance on our LOP/LOP as an indication on how you’ll perform on theirs.”

Jim spoke up. “This is a new concept to us, William. I think we’ll have to discuss this among ourselves after the meeting. Was that pretty much it?” Jim’s voice trailed off, hinting that Jim hoped William didn’t have anything further to discuss on the agreement.

“The only other thing I’d hoped to see in the contract is MANA’s clause that extends termination terms based on service,” replied William. “After some period of time, the termination period becomes more than 30 days, but that’s not a deal breaker,” he said, implying that he placed more weight on the other contract issues he’d raised.

“There is one more informational document I’d like to share with you,” William said. “It’s another MANA document, but I’ve adjusted it to better fit the situation where a manufacturer is considering adding reps for the first time.”

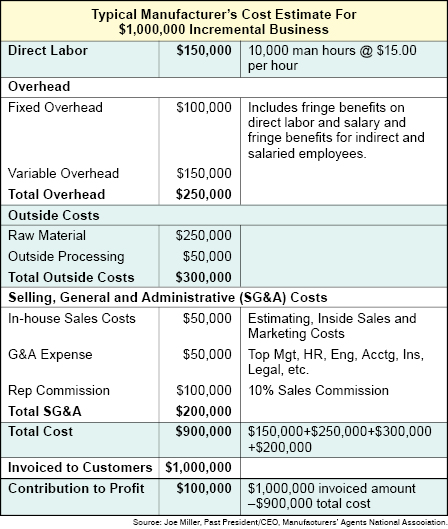

William handed copies of the document to Joe and Jim. “The major assumption I’m making,” said William, “is that the reason a manufacturer is looking at hiring a manufacturers’ rep is that he or she is running his or her factory at less than full capacity. A manufacturer whose factory is running at full capacity usually has other problems that take priority over trying to add new sales, so these figures are based on a situation where a manufacturer is interested in reps as a way to make use of some of their excess manufacturing capacity.”

“I’m with you there,” said Joe, his interest piqued by the idea that a rep could fill his excess capacity. “We could easily fit new orders into our existing production schedule, and I sure wouldn’t mind running a second shift if orders could justify it.”

“Then let’s look at this document,” said William. “This is how a typical manufacturer might break down the costs and benefits to his or her company of a million dollars of incremental business that a rep brought in.”

Joe seemed to perk up when William said “a million dollars.”

“At least I’ve got his attention,” William thought to himself. “Based on the manufacturer’s worksheet, there is a $100,000 profit,” said William.

Joe interrupted before William could continue. “This looks pretty generous to the rep, if you ask me. You’re making $100,000 and the manufacturer is making $100,000. Why should the rep make as much as the manufacturer?”

William was patient. “Remember the spreadsheet we looked at together earlier. The manufacturer is making $100,000 net profit. The rep receives a $100,000 gross commission, but that isn’t $100,000 in profit. The rep company makes about three cents profit on each dollar of commission, so what we’re talking about is $3,000 profit for the rep company against the manufacturer’s $100,000 profit, which doesn’t seem out of line.”

“OK, I see your point,” Joe admitted.

“The good news to the manufacturer,” William continued, “is that his contribution margin from this business is a lot more than $100,000.”

Joe’s forehead wrinkled, and Jim cocked his head to one side. Joe relied on accountants to handle the books, and it had been a long time since Jim had been in an accounting class.

“Let’s look at this spreadsheet again,” William said. “The contribution margin of this order is just a way to measure the difference to the manufacturer’s bottom line between taking the order and not taking the order. So what we do is compare what the manufacturer’s financials would look like if the order was taken with what they would look like if the order was not taken. The difference is the contribution margin.”

“Is that different from the estimated profit?” Joe asked.

“Absolutely. Let’s go over the statement line by line,” William replied.

“I don’t see why, but go ahead,” Joe allowed.

“Starting with line one,” said William, “direct labor is a cost that is a direct result of the new business, so it stays on the estimate. Fixed overhead, on the other hand, is something the manufacturer has to pay whether he takes the new order or not. As a fixed or sunk cost, if the manufacturer didn’t take this order, he or she still would have to pay this $100,000 — it would just be spread over the rest of that manufacturer’s orders. So, say you were doing 19 other $1,000,000 projects and your total fixed overhead was $2,000,000. You’d spread that fixed cost over those 19 jobs at $2,000,000 / 19 = $105,263.16. Now you’re spreading that fixed overhead over 20 jobs and your fixed overhead is $100,000 per job, but that $2,000,000 in fixed costs is a sunk cost that you’d committed to spend even if you only did one project that year. Taking this job didn’t add any new fixed costs, it just lets you spread the accounting for those fixed costs over a larger base of orders, so I’m going to strike through the $100,000 fixed cost on this estimate and write n/a for ‘not applicable.’”

To be continued next month.

MANA welcomes your comments on this article. Write to us at [email protected].